ABOUT

Juliette Murphy is a multidisciplinary artist who works in printmaking, painting and performance. She has lived in Catalunya, Spain for over 30 years and has shown in multiple exhibitions in France, Spain, Britain, the USA, and Portugal.

Latest projects include Qui mira qui, at the Sala Municipal, Maçanet de Cabrenys (2025), Telepathic duets with Birds in the Head, Centre d’Arts Santa Mònica, Barcelona (2025), Mama, International Festival of Contemporary Art, Madremanya (2024), Empordanesos (2022), Homatje Forugh Farrojzad, 13 Festival Pepe Sales, Girona, La Dona La Terra, Museu de Quart, Girona (2020); Resorgir – El poder de la Medusa-Vibra, Maleïda Estampa Gallery, Barcelona, Empordonesos, Figueres, Art i Gavarres (amb Petra Vlassman) Girona.

RELATED TEXT IN ENGLISH

I was born fifteen years after the end of the Second World War in the middle of the Cold War, and right up until I left home at nineteen, my parents made some comment about the war every day. So ‘knowing’ about the past came naturally to me, like learning to ride a bike: I knew that one grandfather fought in the trenches of the First World War, that the other grandfather left Bordeaux in the last British submarine, that my grandmother’s flat was destroyed in the bombing, that my mother was evacuated from London with a gas mask to an unknown destination. As I read a lot, I went back in time, and the history and events of the First World War, and of the Spanish Civil War,

came to me via the poets: Siegfried Sassoon, Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen, Laurie Lee, Stephen Spender, John Cornford… In the end, the immense, terrible history of the 20th century has ended up forming an underlying stratum, permanently latent in my subconscious.

My parents were artists and the house was full of paintings, plates, ceramics, books, English and Japanese prints in an environment full of antiques. Everything was art and art was everything. There was no talk of ‘isms’ but of line, rhythm, shape and volume, appreciations which accompanied any criticism about any artist, in ongoing conversations that intertwined the prosaic everyday routine. This sedimentary layer also lies within me.

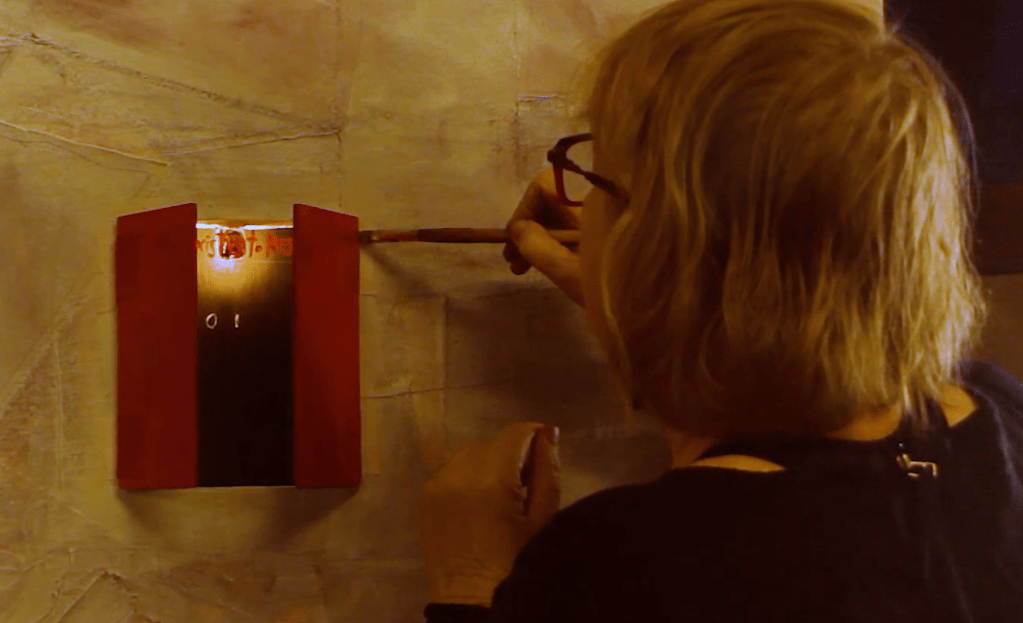

Part of my work develops almost instinctively or viscerally, in connection with a state of being. Other works come from my connection with the world here and now. They respond to ongoing intellectual concerns, and are interrelated, but not necessarily in chronological order. My work process incorporates the physical, the tactile: I like to use my hands. I am inspired by materials of all kinds but have a predilection for natural or commonplace elements: pigments, gum arabic, paper, flour, salt, cow dung. To create is to play and investigate; drawing is vital. From the original thought which may erupt in a flash of inspiration, my ideas begin to take shape and grow, generally from marks first sketched on paper.

The influence of other artists, poets and writers has always been magical: their works speak to me intimately, through the centuries; they transcend time, they are from you to you. Creativity is the engine of our existence, and it is the only thing that remains of our history.

I have never tried to follow a particular way of working that has to be automatically recognizable as mine. I reject the notion of «signature» as a stamp: it’s a concept that conditions and limits creativity. Nor have I distinguished between male and female artists, but simply considered myself artist. However, despite this personal belief, of not differentiating artists by gender, deeper reflection on the consideration of myself as a woman, and of our identity as women artists in the world, has ratified my ideas.

An overview of the last two thousand years of history, dominated by monotheistic religions predominantly expressed in the West through Jewish and Christian beliefs, reveals an underlying discrimination towards women: their intellectual and creative autonomy has been purposefully relegated to a secondary role, and their existence pigeonholed in simplistic role models. Two millenia of deliberate vexatious treatment has insidiously penetrated all levels of society, and still exists.

Since this reality was documented and highlighted in conclusive manner by

philosophers and intellectuals such as Simone de Beauvoir, Kate Millett, Merlin Stone or Helene Cixous, among many others, I took it for granted that women and men coexisted in conditions of increasing equality. These conclusions have proved erroneous. In view of recent history, both political and scientific, it is evident that we must continue fighting to reclaim the voice of women in a world which remains in thrall to a patriarchal system.

The conquest of public space by women, their education, the recognition of their voice and the importance of their opinion are more relevant issues now than ever. On our planet Earth, during the last fifty years, diverse scientific advances and political upheavals, a priori disassociated, have resulted in the negation of physical visibility and participative action of women in society, to the extent that their very existence is threatened. Amongst a multitude of factors, some are particularly grim: the technological advances in ultrasound whose use in emerging economies causes the selective abortion of thousands of female fetuses; the absolute reversal of women’s freedom in the Middle East that has reverberated throughout the West; and the female infanticide that causes a dangerous gender imbalance for humanity.

On the internet there is a resurgence of retrograde stereotypes in the portrayal of women, whether ‘real’ or fictional. Recycled for a young and predominantly male market, archaic and misogynistic prejudice disguised as upbeat contemporary freedom bombards the public. Despite all the efforts of women’s movements, particularly from the 1970s on, we are now confronted by the fact that today’s society is dominated by stereotypes of her as a submissive, inferior, silenced citizen, or merchandize, orrampant, depraved sexual animal.

The exponential increase of these primitive, retrograde stereotypes forces us to become more articulate as artists in order to make our work visible and valued, given that it generally remains unknown among the public. It is our obligation to achieve the transmission of our values so that our contributions as artists are known to the generations that follow. More than ever we must claim the reality and visibility of our existence. We form half of our society and we have a voice.

My proposal as an artist to myself has been to try to understand and explain

something of my life and my deep beliefs in the best way I can. The summary of these long years of work reveals how many of my works, whilst they respond to the world of the here and now of my lifetime, address questions for which we have no answer: our existence, the mystery of birth, death. And over the years, what once seemed way back in time, art that dates back more than 20,000 years, such as the Vénus à la Corne or the Venus de Willendorf from the Paleolithic Age, now resonate with a visual immediacy that shows how anonymous artists from a remote past can inspire us and how the essence of their work may even indicate paths yet to be discovered.

RELATED TEXT IN SPANISH

Nací quince años después del final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en plena Guerra Fría. Durante mi infancia y juventud, y hasta que me marché de casa a los diecinueve años, cada día había algún comentario de mis padres sobre la guerra. Así, mi conocimiento del periodo me vino de manera natural, como quien aprende a montar en bicicleta: sabía que un abuelo hizo las trincheras de la Primera Guerra, que el otro abuelo salió de Burdeos en el último submarino británico, que bombardearon el piso de mi abuela, que mi madre fue evacuada de Londres con mascarilla de gas a destinación desconocida. Como leía mucho, iba remontando en el tiempo, y la historia y los acontecimientos de la Primera Guerra Mundial, y de la Guerra civil española, me llegaron por los poetas: Siegfried Sassoon, Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen, Laurie Lee, Stephen Spender, John Cornford… Al final, la historia del siglo XX tan inmensa e inagotable ha acabado formando una capa estratificada subyacente, latente en permanencia en mi subconsciente.

Mis padres eran artistas y la casa estaba llena de cuadros, platos, cerámica, libros, grabados ingleses o japoneses en un entorno lleno de antigüedades. Todo era arte y arte era todo. No se hablaba nada de ‘ismos’ pero si del trazo, ritmo, forma y volumen. Estos matices acompañaban cualquier discurso sobre un artista, en conversaciones continuas que entrelazaban la prosaica rutina diaria. Esta base también yace en mi interior.

Una parte de mi obra la realizo de manera casi instintiva o visceral mientras que otras obras proceden de la interconexión que tenemos con la actualidad, y responden a inquietudes intelectuales que evolucionan, relacionadas entre sí, pero no necesariamente en orden cronológico. El proceso incorpora el físico, y el físico incorpora el táctil y las manos. Me inspira materiales de todo tipo aunque tengo una predilección por elementos naturales y cotidianos: los pigmentos, la goma arábiga, el papel, la harina, la sal, la boñiga. En el juego de base el dibujo es vital. A partir del pensamiento o la chispa, o ambos a la vez, mis ideas empiezan a tomar forma y se construyen a partir de su visualización física.

La influencia de otras artistas, poetas y escritores ha sido fundamental: sus obras me hablan íntimamente, a veces a través de los siglos, de tú a tú. La creatividad es el motor de nuestra existencia, y es lo único que perdura a través de nuestra historia humana.

Nunca he intentado seguir un modo determinado de trabajar que sea automáticamente reconocible como de mi autoría. He huido la “firma” como sello ya que me parece que nos condiciona y limita la creatividad. Tampoco he distinguido entre hombres y mujeres artistas. Me he sentido como un artista más y punto. Sin embargo, a pesar de esta exigencia personal, de no aceptar que existen diferencias entre artistas por género, he ido ratificando mis ideas hacia una mayor reflexión en torno a la consideración de yo mujer y de nuestra identidad como mujeres artistas en el mundo.

Cualquier reflexión desde una visión general, sobre el rol de la mujer durante los últimos dos mil años de judío-cristianismo revela una triste evidencia: su autonomía intelectual y creativa ha sido relegada a un papel secundario, y su existencia ha sido encasillada de manera primitiva mediante un tratamiento vejatorio cuyas raíces han penetrado de manera insidia a todos los niveles de la sociedad, y siguen ahí.

Esta situación parecía haberse combatido de manera fulminante gracias a escritoras como Simone de Beauvoir, Kate Millett, Merlin Stone o Helene Cixous, entre muchas otras; a partir de los años ochenta yo ya daba por sentada que mujeres y hombres existimos en condiciones de creciente igualdad. Me doy cuenta ahora que fueron conclusiones erróneas. A la vista de la historia reciente, tanto en el político como científico, es evidente que hay que seguir luchando para reivindicar la voz de la mujer en un mundo dominado por un sistema patriarcal.

La conquista del terreno público por la mujer, su educación, el reconocimiento de su voz y la valorización de su opinión son cuestiones más relevantes ahora que nunca. En nuestro planeta Tierra, durante los últimos cincuenta años, debido a avances científicos y revueltos políticos,a priori desasociados, vemos como los resultados de esta sistema niegan hasta la visibilidad física y participativa de la mujer en la sociedad, hasta su propia existencia. Entre tantos otros factores, algunas realidades aberrantes destacan: los avances tecnológicos en ultrasonidos cuyo uso en economías emergentes causa el aborto selectivo de miles de fetos femeninas; el retroceso absoluto de las libertades de la mujer en Oriente Medio que han repercutado en todo Occidente; y la infanticida femenina que provoca un desequilibro de género peligroso para la humanidad.

En la Web, símbolo de libertad digital y máxima expresión de la revolución tecnológica e informática, encontramos viejos prejuicios misóginos que están siendo reciclados en proyecciones de la mujer – sea ‘real’ o sea ficcional – disfrazados bajo una capa de contemporaneidad. A pesar de todos los movimientos para la liberación de la mujer que conocimos a finales de los años 70, volvemos a ver, atónitas, ahora, que la sociedad actual está dominada por estereotipos de ella como ciudadana sumisa, inferior, silenciada, o persona sexual desenfrenada, incluso depravada.

El aumento exponencial de estos estereotipos primitivos y retrógrados nos obliga a una mayor articulación como artistas para visibilizar y reivindicar nuestro trabajo que sigue desconocido por el gran público. Es nuestra obligación conseguir la transmisión de nuestras valores y aportaciones a las generaciones que nos seguirán. Más que nunca debemos reivindicar la realidad y la visibilidad de nuestra existencia. Formamos la mitad de nuestra sociedad y tenemos voz.

Mi propuesta como artista a mi misma ha sido de intentar entender y explicar algo de mi vida y de mis creencias profundas de la mejor manera que puedo. El resumen de estos largos años de trabajo releva como muchas de mis obras, si bien responden a la particularidad de nuestro tiempo, tratan los interrogantes para los cuales no tenemos respuesta: nuestra existencia, el misterio del nacimiento, la muerte. Y con los años, lo que antes me parecía muy remoto en el tiempo, el arte que remonta más de 20,000 años atrás, como la Vénus à la Corne o la Venus de Willendorf del Paleolítico, resuenan con una inmediatez visual que muestran cómo estos artistas anónimos de un pasado tan remoto nos inspiran, y cómo la esencia vital de su obra podría enseñar caminos aún por descubrir.